Before diving into the domain of psychological mechanisms and structures, we need to be conscious of our whole approach to the subject—this article can be looked at as a disclaimer for the other articles on this site. We need to be careful when using descriptions of our mental operations because, even the most true and honest understanding of psychological theories can be just as harmful as it can be helpful. Self-knowledge is a tool for insight but it is also a tool for neurosis.

In itself, knowledge is neutral. We can try to learn all we can about what is going on in our brain. We can reason our way to explanations and justifications for our human behaviors. We can use these tools to help us operate in the social world, but as with any technology, this power comes with the responsibility to use it well. Using the tools of psychological knowledge is not a virtue in itself, so where is the virtue found? To answer this, we must dive into the mystery which there are no tools to help us understand, the mystery of Being. What does it mean to be?

What knowledge doesn’t know

With an understanding of neuroscience, we can ask the question that T.H. Huxley asked: “How it is that anything so remarkable as a state of consciousness comes about as a result of irritating nervous tissue, is just as unaccountable as the appearance of the Djin, when Aladdin rubbed his lamp.” You and I cannot understand what it means for us, as an individual, personal conscious awareness by studying the brain. And we do not need to have understood the physical brain and empirical concepts in psychology to realize that it is something different from what we experience in our Being. But we have to question this Being as a reminder of presence.

Michael Tye, in an encyclopedia article discussing this problem, says, “for no matter how deeply we probe into the physical structure of neurons and the chemical transactions which occur when they fire, no matter how much objective information we come to acquire, we still seem to be left with something that we cannot explain, namely, why and how such-and-such objective, physical changes, whatever they might be, generate so-and-so subjective feeling, or any subjective feeling at all.” Our subjective awareness is outside the realm of definition by the standard tools of empirical science and philosophical concepts.

Everyday reflection on the question of being

The world as we know it seems to only exist on the screen of our perception. This means that an external reality for us does not have to actually exist, there just has to be a viewer. This is the argument of brain-in-a-vat or we-live-in-a-simulation ideas. Because we never find a hidden truth that is not observed through the subjective lens, we can imagine the “true” external world as fake, nothing more than a screen made up of imaginary stagehands placing the pieces of the world around us as we look in their direction.

We have a different sort of trust and certainty in what we experience that we don’t have with the belief in unseen truths—like abstract laws of chemistry or particle physics. This is why an abstract law is so hard to grasp when it is not analogous or observable in everyday experience. Our experience be controversially placed as the top priority in how we can live our lives. I do not mean this in an egocentric or solipsistic theory, but an acceptance that we are stuck in the single, limited sensory perspective and must contend with that. We have no other access point to the world.

There is no reality beyond what you are perceiving

All we can know with a certain warmth, with a unique degree of importance and trust, is the present experience. Simply gaining an understanding of the human mind or our own does not necessarily help us change the space of subjective existence. Knowledge causes us to notice our misperceptions and mistrust and reinterpret other perceptions. This can be good, but not sufficient on its own. Being, and being present, is realizing that there is nothing more than what is, now, that there is not conceptualizing of a moment, it is and we must live in it. Without honoring the moments of our subjective, sensory experience, there is no sense in imagining a truer, psychological world.

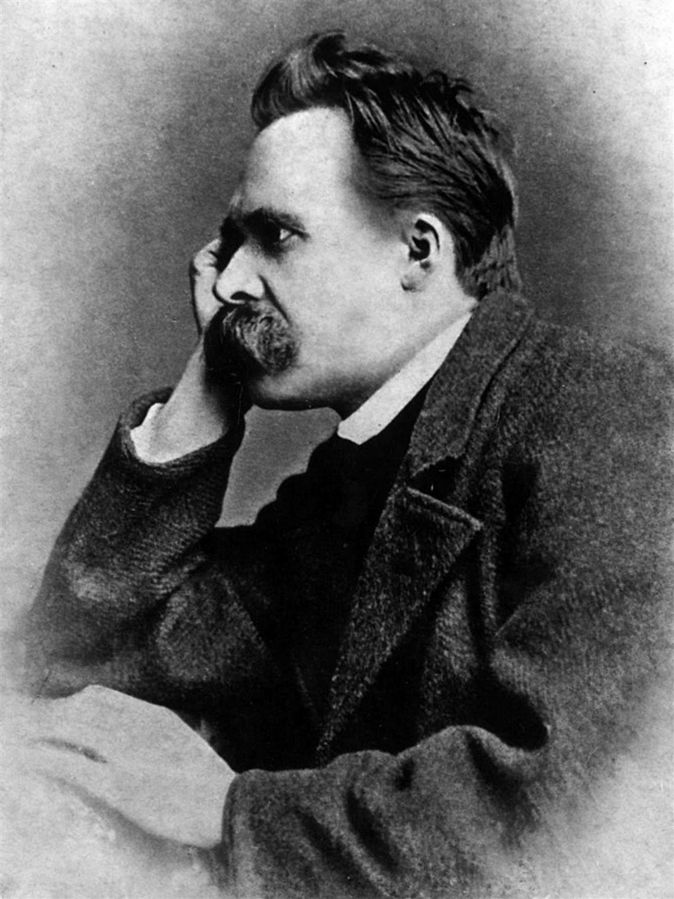

It is our concepts, our ideas of what exists beyond the present, our theories on what the invisible puppeteer is thinking, on how God made the world, that take us away from the present. In this way, we ignore the present appearances, and we see what we think is a higher truth. This is a theme is Nietzsche’s work. He writes on how we create other “truer” worlds to believe in. We do this out of an arrogance that we can know truth beyond the apparent. We aim to ignore the responsibility of the subjective reality staring us in the face, to ignore the present experiences. Like in Plato’s theory of a world of ideals, we find ourselves believing in a truer, perfect, ideal world beyond our perception so that we act like the imperfect, concrete world of experience is of less importance.

“If we no longer believe in the being-behind-the-appearance, then the appearance becomes full positivity; its essences is an “appearing” which is no longer opposed to being but on the contrary is a measure of it.” – Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre

Practicing Presence

What is present is unique, and that is what is, every moment has a uniqueness that our conceptualizing tries to group. Jackson Pollock’s paintings are a snapshot of moments which produces something that cannot be replicated similar to the nature of our Being experience. For a Jackson Pollock painting, everything depended on the present, making it totally unrepeatable, unconceptualizable, and undeniably present. What we want to practice, and therefore create, is something that is present, unique, that comes from some kind of spontaneous self. Pollock didn’t want to create art out of moments that he was removed from the present. And we do not want to create ourselves out of concepts that remove us from the present.

The appearance matters, because it is present, and we are only and always present. We are always present in some way. Even when anxiously ruminating on a past experience, something is still present—an unpleasant thought pattern perhaps. We are present with some other reality, the past or the future or some ideal world.

But there is an apparent one, which takes practice to recognize. When something is not present that is going through one’s mind, it is actually present in a different sense than the apparent sense. It is a sort of schizophrenic presence where perception is a lie, and a “real” world lies inaccessibly beyond perceptions [amazon link to the divided self]. This means that we must realize the problem of our being in order to fully exist in the present. If we cannot exist in the present we cannot exist in a future present. And we start to live in the world of “knowledge,” without concrete joys or pains, all seems objectless and invisible.

In the end the question of being is one which has no obvious answer; it is, however, a practice. Or rather, “the answer is an embarrassment to the question,” as Maurice Blanchot, a French philosopher, phrased it. For us to create abstract answers for the questions of our experience is one way in which we ignore our present experience.

Going forward into psychology

How should you approach the work of psychology from now on?

To be present is to have an acceptance for the apparent and not the underlying psychological mechanisms which this psychological project might seem to espouse. You must be able to use what you learn about how you think not to subordinate the present moment, but to find ways to enrich it.

If anger makes you uncomfortable or do harmful things, psychological theories should not denigrate that anger, simplify it, or trivialize it, but they must help you to understand it in a way that helps you express itself in a wholesome, complex way.

Psychology should not remove you from your present Being, but help you appreciate it, see its complexity and uniqueness.