When someone mentions “the self,” as in self-consciousness, they could mean many different things by it. I try to limit its definition to the part of our mind which has the ability to take abstract symbols like that of language and applies them to our motivations especially regarding future-oriented goals. This does not limit the resulting functions of “the self;” but rather serves as the launching point for many of the other features of self-consciousness.

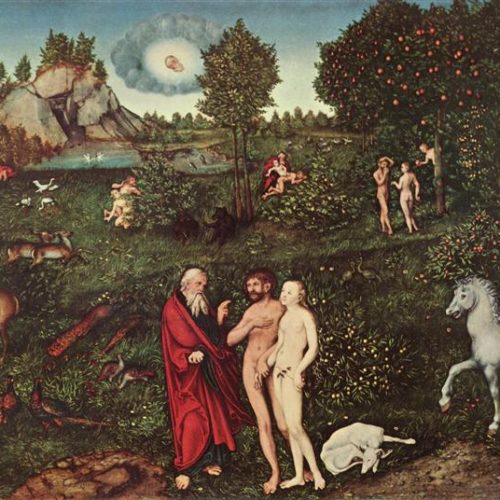

Thanks to our self-consciousness we have abstract thoughts about the future, and these thoughts apply to and redefine the present. For instance, something as biologically necessary as food can have so many different symbolic meanings which draw the food as a present object into more future-impacting symbol. This is seen in how much the food we eat depends on culture and how it is seen socially. It is a long-term, abstracted goal when we believe there are negative effects of not ordering the salad instead of something more appetizing on a first date. The self is actively redefining the present impulse of ordering food.

Self and Self-Control

Knowing what the self is comprised of (expanding from my simple and modest definition) might tell us a great deal about what self-control is. We so often complain about not having the gumption to follow through on what we want—or rather what we say we want! This can have some minor impacts on whether you get a good grade in a class, but it can also create steady habits which change the course of your life. Being continually preoccupied with short-term distractions, will keep you one step behind as the projects and goals pile up

With this article, I aim to help you to organize the idea of self, which is beneficial itself, but this information can readily be converted into advice as it is in one of the most popular advice books of the last century, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey. In the book, Covey emphasizes how to manage time according to what is important and what is often left out as non-urgent yet important tasks like preventing problems, building relationships, planning, and even rest and play. These things appear to someone living minute to minute seem like they are easy to push off to a later time. Covey, when realizing his mistake on forgetting the long-term goal, says “I [was] trying to win the battle, not the war.” This “winning the war” is up to the self and how it defines the world and moves us to achieve the abstract and distance goals.

A Preference Towards the Immediate

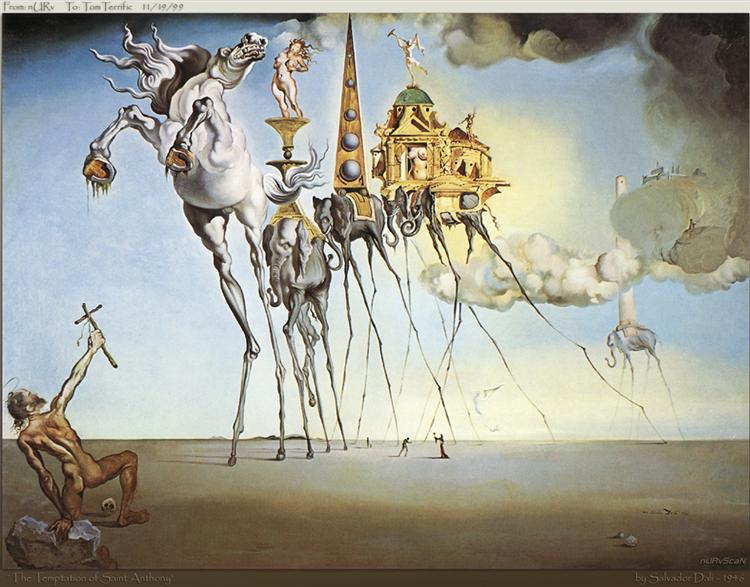

Because, without the self, we are inclined to act in the present moment, the raw impulse is diminished by the self. Abstracting takes away some of the thrust of present motivation. Seeing the calorically-dense burger might not look so appealing to someone who just had a heart attack and is motivated to change his diet. We turn the burger partly into an undesirable abstraction by reading about its health effects of its nutrient content. But often the juicy burger still works its charm. This is because one’s present burger-eating habit is so strong that the abstracting inhibition of the self is either impossible or very difficult.

Our instincts are what have evolved to keep us alive and reproducing, but our self adds an element of planning which can readjust those instinctual impulses. When we are aiming at higher, abstract goals, we are applying more meaning to a future goal than the present one. If the value of the long-term goal is greater than the usual short-term goal, then the inhibition is rather easy.

To illustrate how instinct and self occupy different modes of time-perspective, I will quote a description of an experiment by Margo Wilson and Martin Daly. The excerpt is from Baumeister and Tierney’s book Willpower.

“These evolutionary psychologists began the experiment by asking young men and women to choose between a check dated tomorrow versus a check for a larger amount that could be cashed on a later date. Then, ostensibly as part of an experiment to measure preferences, the subjects were asked to rate photographs of people and cars. . . Some of the young men and women saw photos of the opposite sex who had already been rated . . . as very hot (above 9); some of the participants saw not-hot photos (around 5). Other participants rated pictures of cars, with some seeing hot cars and others looking like clunkers.”

“Then everyone was asked once again to make choices between getting an immediate reward versus a larger reward later”

The result?

“Men who saw photos of hot women shifted towards getting an immediate reward instead of waiting for a larger payoff in the future.”

This wasn’t the case with women who saw pictures of hot men, but one could figure that anything tantalizing might shift someone’s mindset to seeking short-term gains. Present opportunities cause us to ignore future consequences and goals.

The Cost of Self-Control

The sort of self-control which I describe is a limited resource. It is a broad activity and it includes, as summarized by Johnmarshall Reeve, “suppressing impulses, urges, desires; managing and suppressing emotions; controlling and suppressing thoughts; controlling and fixing attention; making decisions and lots and lots of choices; managing the impression one is making on others; and being kind to and dealing with difficult, demanding people.” All of these are done only to aim at a goal which the reward is not currently present.

Especially when these things are performed in the presence of temptations, they have a mental and physiological cost. There is evidence showing that self-control and suppression of emotions uses up glucose quickly in the brain, and that, with low blood-sugar, resisting urges is much more difficult. And we all know what the reaction can be after a long day of inhibiting temptations. It is comfort eating, it is exploding in anger, it is a headache, it is a loss of motivation. There seems to be a limit on the amount we can control.

How, if willpower is a limit resource, do some people become successful at long-term goals and others simply procrastinate? Is it genetic or early development? There is no doubt that these play a role, but there is a change we can make that can put us in better control of our self-control. But can the long-term ever overcome without a cost?

Change the Meaning of the Future to Make It Present

As mentioned, what uses up mental energy is the temptation of the short-term over the long-term, and the following tension. What depletes energy is that you are willing yourself against all biological incentive. But this can be overcome by and change in how you abstractly define things that tempt you. It may never become easy to resist temptations, but, by changing your attitude you may make it easier to continue seeking the more abstract goal.

Even abstract, future-oriented goals, have an instinctual drive. Status, conformity, and security can motivate people to plan for the future, and subordinate present temptations. Of course, planning for the future has no immediate reward! Not yet. But in some ways it does. It is actually rewarding sometimes to plan or to do things which benefit your future.

One study by psychologist Mark Muraven showed that if our needs like autonomy, competence, and relatedness are met by exercising self-control, we are not exhausted by it, but rather, we are revitalized. When the abstract goal activity is supplemented by immediate motivational feedback, we find it easier to aim at longer-term goals. In other words, with changing our definitions of things we can highjack our reward system to feel good when we strive for abstract, future-oriented goals.

Meaning in Life

I do not want to downplay the importance of practice and habit in self-control—it is essential—but I think it is a good start to be able to define what you are aiming for and why you want it so that striving towards it will become much easier. Not only will this help your motivation, but it will also help you understand and adjust your goals by making them more enjoyable in the present.

If we were struggling with eating healthily, we may want to rethink the long-term abstract goals we have set. The symbolic indicators of your goal of health must of course take on a positive value (weight loss, feeling better etc.). But this is all a fairly abstract and inert cause. We are overestimating the motivational power of health for the sake of “health.” You may find that the impression you want to leave on your kids motivates you more. Or that the thought of the chance that your kids or spouse will have to take care of you if you are sick. Social motivators do much more for us than egotistic especially when dealing with long-term goals, because social instincts are not necessary for survival besides in their longer-term benefit. Instincts for friendship are not always useful until you need support (in the abstract future). The new meanings you assign to the present object of desire or the non-present goal will help you design your life according to how you think it.

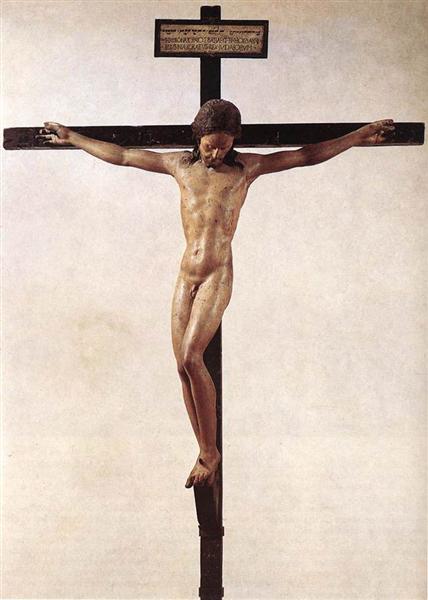

What turns out to motivate you the most is an ultimate meaning to your life. When we find a purpose for our lives, we can use that as motivation to control our actions according to high-minded goals. For good or ill, those who have a pervasive meaning in their life can will their way through anything. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi says that both Mother Theresa and Napoleon devoted themselves to a single goal, derived willpower from it, but arrived at morally very different results.

“He who has a why can bear with almost any how”

Nietzsche

Learning self-control is not all about practice. It is also about finding a good reason for struggle and overcoming temptations. It is as much about inhibition as it is about having a ubiquitous goal in life.