The human psyche reaches unfathomable depths in any age, but we probably understand the least about the foundations laid at the first stages of life. It is a stage that has become so alien to us after all the personality growth and change. Asking what it is like to be an infant is almost like asking the great question of how consciousness itself has come to exist. To explore the situation of the infant we can look to the work of Erik Erikson. Erikson formulated psychosocial development as a continual encounter with crises corresponding to eight distinct ages of life. The first of his stages is the crisis of basic-trust-versus-basic-mistrust, the resolution of which he determined to be the most foundational for the crises of later life.

“It was said that the most basic issue in therapy also is the issue of trust, that all other issues rested on this foundation and that, failing to resolve an issue on a less fundamental level led back to this issue in the face of which both therapist and client are hesitant.”

Richard Knowles in “Suggestions for an Existential-Phenomenological Understanding of Erikson’s Concept of Basic Trust”

We gain the seeds of an “I” with this trust, the ego is created out of its installation, and therefore meaning can be created and can continue to be created after. This foundational stage permits the very “illusion” that we are stable centers of perception that can have some sort of understanding of the world and that can make sense. And the virtue which we acquire from the navigation of this crisis is “Hope,” an equally foundational trait.

An excerpt from the Mahdbhdrata: “Hope is the sheet-anchor of every man. When that Hope is destroyed, great grief follows which, forsooth, is almost equal to death itself.”

Sudhir Kakar in “The Human Life Cycle”

What is the outcome of this crisis? And further, what is meant by this hope? How is this crisis successfully navigated and what can we do to retrace these ancient steps to strengthen this hope?

The Infant’s Situation and Consciousness

The situation of the early infant is one of complete dependence. Whatever reflexes or impulses the child has are virtually only successful through the mediation of the parent. These instincts are useless on their own. They are also passive in the sense that they require no conscious effort, only the relinquishment of control over the body and allowing one’s “nature” to take over. It is not through the will of the baby that it feeds, but by its passive embeddedness in nature.

“The first demonstration of social trust in the body is the ease of his feeding, the depth of his sleep, the relaxation of his bowels. The experience of a mutual regulation of his increasingly receptive capacities with the maternal techniques of provision gradually helps him to balance the discomfort caused by the immaturity of homeostasis with which he was born.”

Erik Erikson in Childhood and Society

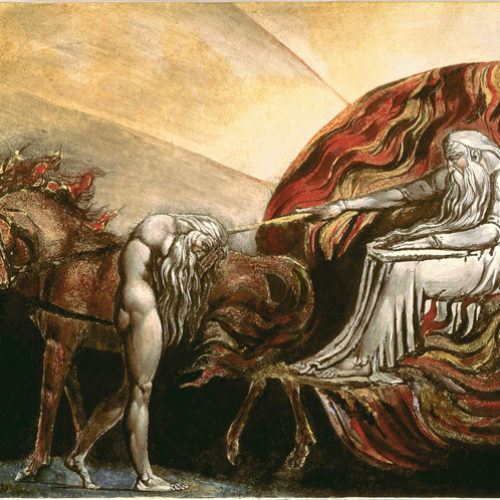

Psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott famously claimed there is no such a thing as a baby, but only a baby-with-mother. At the early points of this crisis, the child has no distinct being, his or her consciousness is solely reliant on the caregiver. If the child, being a creature of reflex, is without the mother the world becomes senseless and chaotic. The emotions that the infant has are global and are best described in the mythology of the Benevolent Mother and the Terrible Mother. Where the mother is calm and the infant can allow its instincts to prevail, the Benevolent mother is present.

There are times, however, where the reliance on the unconscious, passive relationship with the instincts can become meaningless, to have failed or the mother fail to allow the instincts to manifest unconsciously. When those aspects of predictability are gone, basically in the absence of the mother or the presence of the anxious or smothering mother, chaos ensues. And the world seems unreliable, one’s reflexes no longer achieve their aims of feeding and comfort: the Terrible Mother is present, threatening the very existence of the child, literally in terms of the infants dependence to survive, and subjectively, as there is no basis for reliable meaning in the world if one has no means to survive.

Trust and Mistrust: Meaning-Making in the Holding Environment

According to Erik Erikson, the conflict between basic trust and mistrust is the first task of psychological development. This is also the most fundamental problem facing us in life and in therapy, as noted in the introduction. It is what prevents us from saying what needs to be said or doing something that makes us vulnerable but can help us grow. In order to understand the basis of this conflict, we must attempt to look back to the earlier part of life, when the trusting situation was first posited.

The first stage of Erikson’s theory, basic-trust-versus-basic-mistrust, gets its name because of what would have been fragmentary sensorimotor reflexes is slowly found to have repetition in a world that can be trusted. This of course is not merely a somatosensory stage, but a cognitive and social one. This is a trust born out of experience that mom will return, that one exists in an environment that is survivable, and the relationship with caregivers is consistent, contiguous, and similar across separate times. This trust begins with the contiguity of the world and then with the thing that sees the world, the ego.

“Such consistency, contiguity, and sameness of experience provide a rudimentary sense of ego identity which depends, I think, on the recognition that there is an inner population of remembered and anticipated sensations and images which are firmly correlated with the outer population of familiar and predictable things and people.”

Erik Erikson in Childhood and Society

It is the Benevolent Mother experience that provides this early sense of meaning to the child, essentially saying, there is a comforting ground nearby at all times. Somewhere where you can relax and come back to, to surrender to and be with. The child’s experience of trust is in predictability and is demonstrated by being at ease. The meaning created by this is guided through the parent providing a predictable world that the infant can be “held” in where basic learning (such as habituation and associations) occurs.

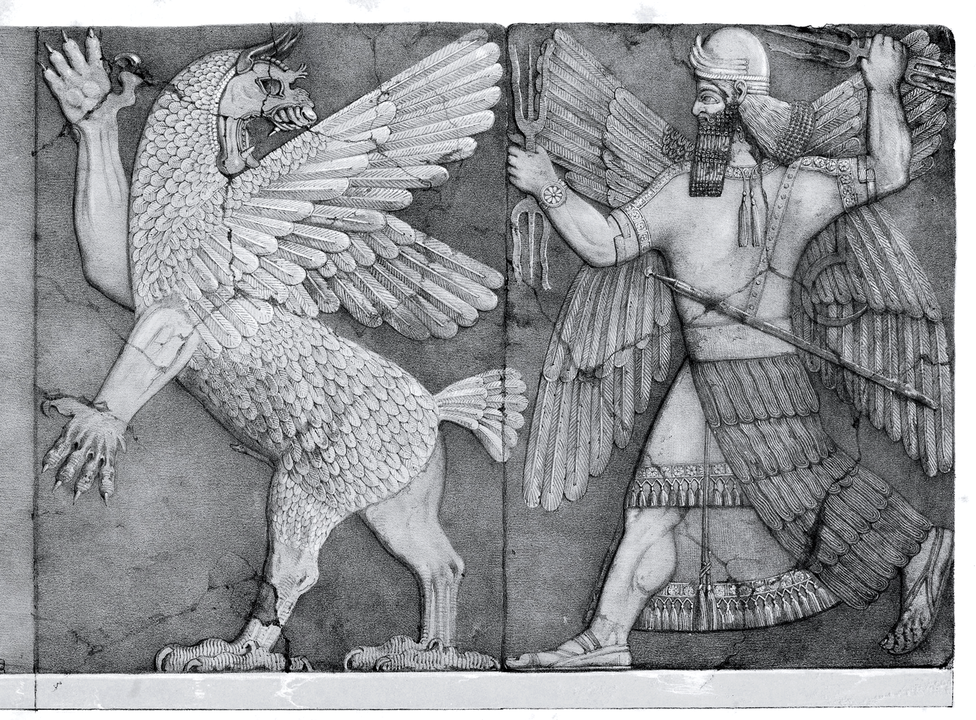

Ego Overcoming Chaos

Creating the conditions for perfect trust are bound to fail. A child cannot, no matter the effort supplied by parents, survive in the pure, effortless bliss of predictability and success with unconscious efforts.

“But even under the most favorable conditions, this stage seems to introduce into psychic life (and become prototypical for) a sense of inner division and universal nostalgia for a paradise forfeited. It is against this powerful combination of a sense of having been deprived, of having been divided, and of having been abandoned—that basic trust must maintain itself throughout life.”

Erik Erikson

To the child the archetype of the Terrible Mother sows the seeds of mistrust. This is a projection placed on the situation of being without the facilitator of one’s sensorimotor instincts. It is the experience of meaninglessness in the infant, where there is no possibility of surrender to what one “knows,” where the world itself is set against one’s existence.

“A successful resolution, that is, a favorable ratio of basic trust over mistrust, gives the developing individual the ontogenic basis of the first and the basic virtue: “hope.””

Sudhir Kakar in “The Human Life Cycle”

The task of the infant is to overcome the abyss of distrust in the world. If a favorable ratio of trust to mistrust is provided by the situation, the child should have no problem using its conscious ability to venture past the world of the known, in areas of perception that one has not yet learned to trust, but may one day understand. The product of sufficient trust is a persistent “I” which is carried from sensation to sensation. The virtue hope is the result of the recognition of the meaning-making effort that comes with adequate trust.

What is Hope?

Encountering the Terrible Mother is inevitable. Even unerring parents cannot maintain an environment that allows total trust in unconscious processes. The infant needs to carry the trust with him or her in order to make sense of what is unknown. The ability to carry the trust is known as hope. Hope, or matured trust, is to be at ease within the ever-present possibility of chaos. This requires attention and adaptations to things not yet explored.

“[Most people describe trust as the experience of] a risk-taking venture, one which was unpredictable, one in which they trusted despite their inability to predict.”

Richard Knowles in “Suggestions for an Existential-Phenomenological Understanding of Erikson’s Concept of Basic Trust”

This helps us to define hope in a way that avoids a common misconception. Hope is not blind optimism—that is immature trust. Hope is the acceptance of the possibility for despair, but having trust in one’s ability to cope with the unpredictability and vulnerability of going beyond the known.

“There can strictly speaking be no hope except when the temptation to despair exists.”

Gabriel Marcel