The feeling of being drained of energy while still having things to do is a feeling I regularly have. The tendency to procrastinate becomes practically inevitable. I hazard to guess that this is not an uncommon experience among anyone who relies on self-motivation to accomplish their goals that they could easily put off for another time. Students, particularly those with fulltime jobs inevitably know the feeling of what it’s like to think of their own lack of motivation as their worst enemy. Each of our efforts at self-control always seems to lead to a rebounding temptation for impulsive gratification in equal or greater measure than the effort at self-control. The amount that we can control our attention and desires clearly seems to be limited, but to what extent and how it can be replenished is still in question.

This feeling is cited in psychological research called ego depletion. The theory describes the apparent phenomenon of a limited resource of willpower, and that, once expended, this resource must be replenished by gratification or time. The legitimacy of the research behind this theory has been under fire from new experimentation techniques and statistical analysis, but we ought to take a look at what might be true to our experience regarding our willpower. Much of the ideas and attitude here reflect a review article by Michael Inzlicht and Brandon Schmeichel called “What is Ego Depletion? Toward a Mechanistic Revision of the Resource Model of Self-Control.”

By looking at these authors evidence-based theories are, and combining it with the question of what the self or ego is, we can see deeper into what comprises “willpower.” It is no mistake that we call ego-depletion by that name, but the theories seem to have little to do with ego or self. Confronting the motivations of the self may help us find the truest way of operating with self-control and knowing how to better live our lives without either exhaustion or laziness.

The Original Theory of Ego Depletion

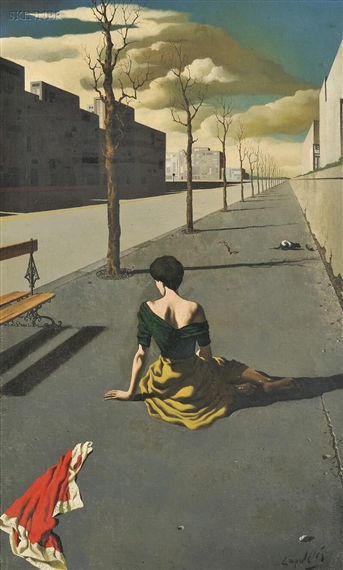

The experience of laziness after a difficult day’s work is practically universal among us. We admire those who, after a hard day of work and continue to work beyond the call of duty. But as we come near the end of each day and recall the chores we still need to do—but could easily put off—we almost need something to force us into working. The self-motivation required for personal projects, reading, exercise, paying bills, and other forms of keeping the house together diminished almost entirely by the time there is finally time to do those things. Perhaps worse is our laziness to those who deserve our focused attention, but the work of the day turns into halfhearted affection or even frustration towards those who we love. When we are trying to improve our habits, these slips of self-control can ruin all our efforts before.

“Each lapse is like the letting fall a ball of string which one is carefully winding up; a single slip undoes more than a great many turns will wind up again.”

William James in The Principles of Psychology

Nothing about this phenomenon seems surprising or unique, but a psychological theory has come along that attempts to explain why it seems like we react so self-destructively after a bout of self-control and emotional regulation have occurred. The ego-depletion theory was created and popularized by Roy Baumeister. The basic idea behind the theory is that exerting self-control at one point in time will increase the errors or slips of self-control in a following task.

In Baumeister’s famous experiment, a subject will either have to resist the temptation to eat a radish or a cookie (guess which would require self-control). Next the subject would have to solve a problem that requires focused attention. The result was those who resisted the cookie did worse than those who “resisted” the radish.

The initial conclusion of this observation is that we must have a limited resource of willpower that is used up like gas in the tank. Things which deplete this resource include thought or emotional suppression, focused attention, resisting urges, making choices, tolerating pain or discomfort, or dealing with difficult people. This theory seems to suggest that all of these things have a unified measurable resource that they use up. This theory gained much popularity in its claim that willpower is a limited resource, probably because it seems so true to experience.

But recently the theory has come under empirical scrutiny as the supporting experiments have not been replicable. This leads us to redefine the phenomenon in a way that is more nuanced and coherent with what is known from experimentation. If willpower is not a limited resource, what is going on that makes it appear like one?

A Motivational Model for Ego Depletion

One of the findings that seems to contradict willpower-as-resource theory is that gurgling a sugary beverage was good enough to replenish some willpower, despite it not replenishing glucose (one thing that seems important for willpower). Belief systems, self-affirmations, mood also affect the “resource” of willpower. This clearly shows that there is more going on than a meter of willpower going up and down.

One model defined by Inzlicht and Schmeichel is the process model for ego depletion. It is a far more parsimonious theory that turns willpower from a universal resource to a mode of motivation that can shift according to well-studied rules behavior and motivation, such as operant conditioning. All the experiments which seem to support the ego depletion theory can also be reframed to support the idea that, rather than depleting a resource, use of willpower changes our motivational orientation and prompts us to look for gratification as a reward for our previous self-control. This is similar enough to the original claim, but different enough to explain the research that rejects the original.

What I found most odd about the theory of ego-depletion experiments is that it treated self-control as the default, and attempted to explain why we fail at it as if self-control were the default. The experiments that tested this assumed that the subject would be totally motivated to endure pain, resist pleasures, suppress emotions, for no other motivation besides being a good subject in an experiment. Why would you expect a person to put more effort in if their self-control was for nothing? Once a subject finds out that there is no reward, why not expect them to slack off in the second task. It would not surprise me if willpower was truly a limited resource in the context of these experiments, but willpower used in our lives is not done arbitrarily with no expectation of gratification. The question should not be a question of why people cannot expend limitless energy on self-control. It should be why they ever resist present impulses and temptations.

The Self in Self-Control

In a previous article, we defined the self as being derived as an amalgamation of long-term goal commitments. If we are to have a long-term goal, we must have a conception of ourselves and have an idea of how this self can reap the benefits of that goal. This applies directly to self-control because it always is in the effort to access a higher goal than the present, impulsive goal of indulgence. To suppress emotion is to determine that the expression of the emotion is deleterious to one or many of the goals that you have for your long-term self.

What gives energy the self or long-term motivation is the attitude to the future self, the importance of the goal (defined by one’s present emotions towards it and other competing goals), and one’s feeling of when striving to the goal. There are deeper psychological needs that can be met by striving for goals for the future self. Feelings of competence, control and community give self-control intrinsic value that’s importance will be discussed later. What does not seem as relevant is how much willpower you’ve recently spent or how much you’ve rested since then. Let us look further into what this means to improve our abilities to control ourselves.

Consider how we would accomplish any long-term goal: we subordinate the present enough to create a better future, but not so much as to neglect the present self and arrive at the future moment bitter and worn. Our present self is the only gateway to a future self so if we are going to have a good future self, we have to maintain some level of enjoyment in the present self. It may also be a sign you are after the wrong long-term goal if it destroys you to pursue it and getting closer to the goal is no longer exciting.

If we are to engage in self-control, we may as well make it for a worthy cause. Many instances of willpower, if not rewarded (or if punished), will not lead to further willpower, but the gaze will be set on the present. It is not willpower that depletes itself when used; it is willpower used for undesirable or regrettable causes. You may put up with a difficult person and suppress your emotions, but that will not lead to any desirable result, thus the effort is for nothing, you are not gratified by your effort. You may then act impulsively to make up for the thankless self-control.

Meaning in Self Control

Our lives can greatly improve if we figure out how to find infinite self-control without having to result in impulsivity to replenish it. Or we can allow the right kinds of reward to replenish our wills. One way of looking at this is to decide what one’s authentic self is. According to the ideas of Hal Hershfield, we can work towards the present self or many future ones, and the future ones can occupy many different possible situations and social roles. Hershfield says there is no obvious way of telling which self is more authentic, the present or later self, but what we certainly figure out which selves we do not want to work towards.

To exert willpower on something that one will later regret is a meaningless sort of self-control. Becoming deliberate about the discipline and constraints we make is what actually allows willpower to last without need of impulsivity to be replenished. A noble goal supplies its own intrinsic motivation. We feel happy excitement when we feel like we are getting closer to a meaningful goal. When we do good work, feel competent, work with others, and feel in control, our willpower is replenished. And simply moving towards a meaningful goal is enough to excite the will into working overtime.

“He who has a why can bear with almost any how”

Nietzsche

Deliberate goal-making is reminiscent of Henry David Thoreau’s entire motivation behind his experience at Walden pond saying, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately…” He placed constraints upon himself and did not waver because the treasure of those efforts was worth it to him.

If you make sure the future self you are working towards is one that you really want to be working toward, instead of exerting self-control only to make matters worse or no better, then persistent motivation will find its way. It is not the effort itself that is draining, it is effort that does not lead to any hope of reward. Meaningless effort is a limited resource, but meaningful work towards well defined goals is boundless.